People are known for making quirky, bad and just plain silly choices. So why do we expect them to behave rationally? This article discusses how consumers make decisions from a behavioural economics perspective. We briefly explain the “fast and slow thinking” model of Daniel Kahneman. Then we offer two real-world success stories, share seven behavioural biases you (or your agency) should be using to influence decision-making, and wrap it all up with tips on how you can apply this learning to the management of your pharma brand.

What is behavioural economics?

Behavioural economics blends psychology, economics and the scientific method to examine how humans make decisions. It asks questions such as “Why do people buy a bag of candy instead of a bag of vegetables when they’re trying to lose weight?” and “Why do people buy $4 lattes when they’re trying to save money?” The reasons are often irrational, and that’s the basic insight of behavioural economics. Our behaviour is guided, not by the perfect logic of a super-computer that can analyze the cost-benefit of every action, but by our very human, social, emotional and sometimes fallible brain.

Behavioural economics has produced two Nobel prize winners, inspired blockbuster movies (think Moneyball), and resulted in best-selling books like Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions by Dan Ariely, Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein, Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking by Malcolm Gladwell, and Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman.

In Thinking Fast and Slow, Kahneman—who happens to be one of the Nobel prize winners—popularized the idea of “System 1” and “System 2” thinking as it relates to how we make decisions. System 1 thinking is fast, automatic, intuitive and often unconscious. It uses mental shortcuts and biases to make choices as quickly as possible. System 2 thinking is slow, deliberate and analytical. We have to work hard to weigh pros and cons objectively, hence System 2 thinking is more difficult for us to do.

Why does behavioural economics matter to brands?

Researchers have found that consumer decision-making is generally 70 per cent emotional (System 1 thinking) and 30 per cent rational (System 2 thinking). In contrast, brand managers and marketers often act like the people we’re trying to reach are weighing each choice carefully. It’s easy to see why. We’re spending upwards of 70 hours every week thinking about our brands and products, and lose sight of the fact that our consumers are spending seven seconds on most decisions.

Our belief (or maybe it’s a wish) that consumers are rational has an influence on our marketing toolbox. In traditional market research, we ask participants directly about their purchase intent and their reasoning. We explore “what-if” scenarios. We ask them to explain decisions they’ve already made. While consumers actually make snap decisions, marketing research treats them as shopping savants. Then we use this potentially inaccurate information to make important strategic decisions about our brands and campaigns.

We’re trying to get System 1 thinkers to rationalize their decisions in a System 2 way. Instead, we need to think like System 1 thinkers from the outset.

Of course, sometimes we do. Long before the discipline of behavioural economics had a name, we were using some of the approaches. “Three for the price of two” offers and extended-payment layaway plans became widespread because they worked, not because marketers had run scientific studies showing that people prefer a supposedly free incentive to an equivalent price discount or that people often behave irrationally when thinking about future consequences. Now it’s time to apply the principles of behavioural economics to our work in a systematic way. Until they’re embedded into a framework, the ideas will be talked about more than acted on.

What can happen when you think like a System 1 thinker?

There are many examples of the power of using System 1 thinking to influence behaviour. Here are two that apply to marketing.

Weighty decisions. A study conducted by the Yale Center for Customer Insights and the Google Food Team examined how people can be nudged toward healthier eating. Researchers found that Google employees who poured their drinks at a beverage station 6.5 feet from a snack bar were 50 per cent more likely to grab a snack than those who filled their glasses at a beverage station 17.5 feet away from the snack bar. For male Google employees, 11 feet of proximity correlated with gaining one pound of fat per year. The moral of the story? Simply moving food further away from the drink station deterred snap (or is that snack?) decision-making.

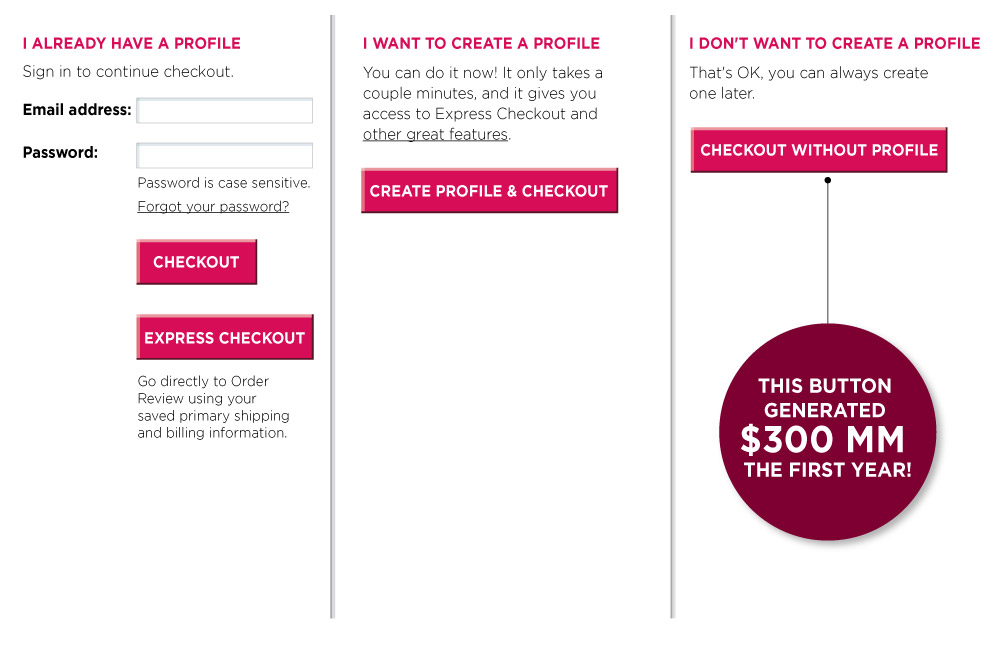

The $300M button. In the early days of Amazon, customers had to log in or sign up before they could purchase an item. Both options require cognitive effort; the first requires remembering a username and password and the second entails recalling and typing personal details. To remove these behavioural barriers, a ‘guest checkout’ function was added that allowed people to skip creating a profile. The result? Annual revenue increased by $300M in the first year. (The punch line? People who checked out as guests still had to enter the same information in order to process payment as they would if they had opted to create a profile—they just didn’t know it!)

7 behavioural biases to use in marketing

System 1 thinking is driven by beliefs, biases and instinct—influences such as peer pressure, ego, habit, incentives, gut feel, fear of loss, who the messenger is, and more. Here are seven biases that have been used successfully to influence consumer behaviour.

- Anchoring. Consumers will rely heavily on the first piece of information offered to them and use it as a reference and benchmark from that point on, whether it makes sense or not. Marketers can present a high price for one option that can influence subsequent consumer purchases by making other options seem cheaper. For example, an online store could offer a $399 coat that's been marked down to $99, creating the idea that an expensive—and therefore more desirable—coat is now a great buy. One of the most famous examples of this bias being used to influence behaviour is the campaign by De Beers' to set an anchor for spending a month’s salary on an engagement ring (in the U.S. it was two months). Surely, this ploy was laughable. Why listen to someone with a vested interest in you spending heavily? Because we aren’t rational. And because of anchoring.

If you communicate a number, however irrelevant, it influences the thought process of the listener. Even though most ring buyers recognized a month’s salary was too much, it served as a starting place for their deliberations. The results were exceptional. De Beers’s U.S. diamond sales rose from $23M in 1939 to $2.1B in 1979. Even accounting for inflation, that’s a 19-fold increase.

- Social proof. Customers look to other people for information on what to buy or what service to use. Marketers can solicit customer feedback and promote testimonials in order to provide this social proof. When consumers know that a product, or even a behaviour, is popular, its appeal tends to increase. There are many famous examples of social proof being used successfully to influence behaviour. Think of Amazon, which tells you what other, similar, customers have bought. Influencer marketing is another example of social proof in action.

- Loss aversion. Consumers are more willing to take risks in order to avoid losing things than to pursue gaining things. In fact, the psychological pain from losing is double the pleasure of a gain. Marketers can promote products in a way that demonstrates their purchase will help them avoid loss. For example, a marketer promoting thermostat upgrades might say, “Stop losing $100 every year in energy by buying our programmable thermostat!” instead of, “Save $100 a year in energy by buying our programmable thermostat!”

- Default. Defaults are preset options or courses of action. Because consumers would rather avoid losing things than take a risk for a gain, they’re unlikely to defect from a default option. Furthermore, if marketers give customers that default option, they’re helping to define the customer’s ownership of the default. Now that they value that option more, they’re less likely to part with it. Marketers can use defaults to persuade customers to receive email updates and offers, but should be careful not to opt customers in to so many options that they feel taken advantage of.

- Choice overload. When consumers are presented with too many options, they can become overwhelmed, leading to unrealistic expectations, decision-making paralysis and unhappiness. In a study of jam purchases at a supermarket, 30 per cent of shoppers who tried samples made purchases when presented with a choice of six jams, while only three per cent of shoppers ended up making a purchase when presented with a choice of 24 jams. Additionally, the shoppers who chose to buy from the selection of six jams reported greater satisfaction with their purchases. Thus, offering fewer choices to consumers can increase sales.

- Framing. How marketers set the context and present information can influence consumers’ decisions. Marketers have found that including a few cheaper options increases the likelihood that consumers will purchase a more expensive option. The impact of framing can be observed in a grocery aisle, where products are organized and displayed by customer preference rather than price. Marketers can also influence shoppers’ purchasing decisions by placing promoted products in places consumers are more likely to buy from.

- Decoy effect. Consumers’ preference for one option over another can change when a third, similar but less desirable, option is presented. Economists found that customers were more likely to choose a more expensive pen over $6 in cash if a third, less expensive pen was introduced as an option. Thus, you can introduce products into the market that nobody chooses but nevertheless have effect on what people ultimately choose.

How to apply behavioural economics to your pharma brand

Whether you’re marketing to doctors to prescribe your drug, consumers to purchase your product or patients to take action on your unbranded website, you need to understand “fast thinking” and “slow thinking” principles if you want to trigger the right motivations at the right times to nudge people in the right direction. When these behavioural theories are applied to a healthcare setting, what we often see are improved outcomes. At the very least, an awareness of these biases will prevent our efforts from being undermined by them.

You can apply these principles to create your opt-in enrollments, choose the right wording for a call-to-action, and design programs.

When it comes to influencing the behaviour of healthcare professionals and consumers, it’s time we stopped thinking slow and started thinking fast. Use the biases and shortcuts we all employ when making decisions to become the “no-brainer” choice in the marketplace—or risk losing your customers’ attention. (P.S. We just used loss aversion on you!)